we were standing in that quiet gallery at the frye art museum in seattle, the light falling softly on those masks that seemed to breathe and moan in their own slow rhythm, each one carrying a world that had been shaped by hands far more seasoned than mine. i remember how still my body felt in that room, my breathing slow and deep as if anything louder might break the air. it was the kind of stillness that comes when we recognize craft that carries lineage, discipline, and spirit that is not ours to claim, only ours to witness with care. i looked at each mask from every angle, trying to absorb what they were saying. i know some ceremonial masks are worn, and that part of their meaning comes from the body that moves inside them, the way a dancer leans into the animal or ancestor pictured. i tried to feel my way toward that. it left me wanting more and feeling wrong for wanting it.

i grew up in france, where stories about native americans were handed to children like candy. they came wrapped in romance and distance, not in truth. in those westerns, classrooms and cartoons i learned to idolize an idea rather than a people, a flat myth rather than a living culture. i carried some of that with me for years without knowing the harm it could cause. memory teaches slowly, and sometimes it teaches by showing how small our early understanding really was.

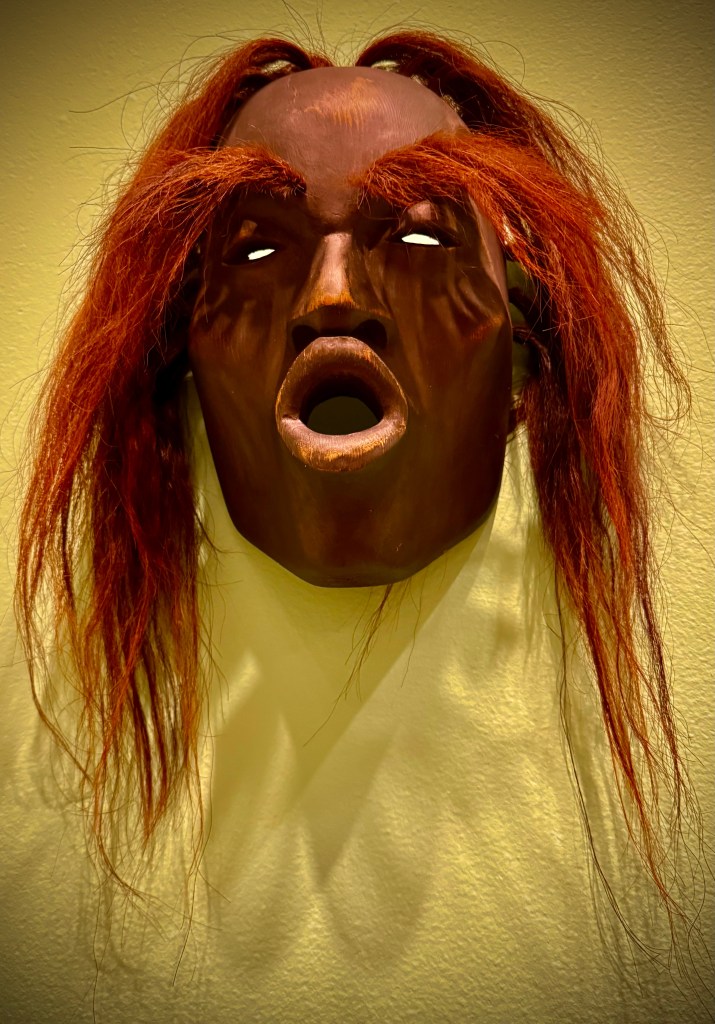

standing in front of Beau Dick’s masks brought me back to that gap. the carvings were massive, fierce and tender, intricate and alive. they were colorful and carried the weight of torn ideals, destroyed dreams, lost country.

Beau Dick was a master carver of the Kwakwaka’wakw people, a visionary whose work reached far beyond the sculptural. he led dances, reclaimed traditions, spoke out against suppression, and used potlatches as acts of political resistance and cultural renewal. his art was rooted in survival and in the steady insistence that memory is not something to be kept quiet. he even burned masks that were still on active exhibit as part of a ceremonial act, reminding the world that these works live within cycles larger than display. he rallied his community behind its own identity and offered his strength to movements demanding dignity and recognition. to see those masks was to see that history made visible in cedar and pigment.

that day in the frye, the masks felt like something made by people who carve not to show skill but to hold responsibility. i noticed the grain bending around deep cuts, the way each face seemed to rise out of the wood as if the carver had coaxed it forward rather than imposed a form. the wood felt like a collaborator. as someone who now spends hours at a workbench shaping wood into my own small attempts at form, i felt admiration that bordered on awe, yet it came with a quiet reminder: this is not my tradition, not my story to echo, and the beauty of it is exactly why i must not try.

i kept returning to one mask in particular, its sheer size increasing its force on the viewer. it had a long beard made from horse hair and a presence that felt both human and something older. even from several feet away, i could feel the confidence of the hand that shaped it. the grain curved around the cheeks like something guided more than carved, and the cedar seemed to hold its own breath. standing there, i felt two currents moving in me at once. one came from the careful worker in me, the part that has spent years learning how wood behaves, how it offers itself, how it resists. the other came from much farther back, from that childhood in france when westerns filled the television most weekends, all dust clouds and galloping horses and a familiar storyline where native people almost always lost. even as a kid, something in me reached toward them. i felt a strange kinship with the ones who were pushed back and spoken over. it was an uncomplicated feeling then, the kind children have before nuance arrives, but the seed stayed. i didn’t understand culture. i didn’t understand power. i only felt drawn toward a people who were never given a fair telling on our screens.

later, when i moved to the usa, that old affection collided with the reality of harm, appropriation, and the many ways outsiders can take without meaning to. i had to unlearn my own images. i had to learn how to admire without crossing lines, how to be shaped by another culture’s beauty without trying to reproduce it. and that sometimes means noticing where influence ends and respect begins.

recent conversations with native friends helped me settle that tension a little more. one saw my tattoos, which i had gotten long before i understood how fraught they could be. she didn’t judge. she told me that younger folks in her community sometimes read gestures like mine as a form of respect, a way of carrying care rather than claiming ownership. i know others feel differently, and both truths matter. still, her words softened something in me. there is room for learning, room for accountability, and sometimes room for grace.

another friend read the story i wrote for the library of glad tidings, the one loosely threaded with creation motifs and the sense of a world spoken into being through animals and elements. she said she could see why i would worry. she also said that because i wasn’t trying to profit from it, because i was writing out of affection and imagination rather than theft, it sat in a different place. her response didn’t absolve anything, but it offered perspective. it reminded me that intention, humility, and care matter, and that the right relationship to influence is a living process, not a perfect rule.

so when i stood in front of those masks at the frye, what moved me was not permission. it was responsibility. these works belong to lineages i am not part of. they carry lessons and obligations that were never meant for me to imitate. yet they show how deep craft can go when it is rooted in culture rather than experimentation alone. they ask me to approach my own work with more integrity, more attention, more honesty about where my lines are and why they matter.

i can love the curve of a cedar cheekbone or the tension in a carved mouth. i can let these creations remind me that some stories travel through communities, not individuals, and that reverence sometimes means staying on the right side of a boundary.

in the museum, i found myself thinking about how we move from innocence to intention. when we are young we imitate because imitation feels like affection. as adults we carry a different kind of responsibility. we learn that admiration is not a license. we learn that some practices hold histories that outsiders can love, study, and support, but never borrow. we learn that honoring means knowing where to stop. someone once told me that the hard line for native artists in the pacific northwest is in the shapes and colors used. i don’t know if that is fully true, but it helps trace the boundary, and boundaries matter.

the exhibit helped me settle into that understanding with more clarity. i can be moved by the power of these masks, by the generosity of artists who allow their work to be shown to the public, by the deep histories that live inside cedar and paint, and still know that my own path as a woodworker needs to stay rooted in what is truly mine. influence travels in the body like weather, and we have to learn how to sort admiration from appropriation, respect from desire, and curiosity from entitlement.

what i brought home that day was not a new technique or aesthetic to fold into my projects. it was a reminder that craft is never just craft. it is culture, community, life, cosmology. when we see something extraordinary, we can let it change the way we pay attention without trying to make it ours. we can let it sharpen our sense of care, our humility, our willingness to learn without taking.

i left the exhibit grateful. not inspired in the way that makes a person pick up a tool and try a new pattern, but inspired in the quieter sense that sharpens discernment. more careful. more aware. more committed to honoring what is not mine to touch.

Leave a comment